The Third and Fourth IPCC assessment reports have recognised that natural and anthropogenic aerosols play an important part in climate change.

To better understand the radiative properties and distribution in space and time of aerosols, improvements in both observations and global climate models are needed. The emission, transport and deposition of mineral dust aerosol depend on physical processes on a wide range of scales, and representation of the dust cycle is particularly difficult in models whose resolution may be too coarse to produce the small-scale wind flows which give rise to much of the world's dust production. In particular, observation campaigns over Africa (the world's main dust source) have shown that the orography is crucial in funneling the surface winds around the Hoggar, Tibesti and Air mountain ranges to produce dust from the Bodele depression in boreal winter and from Mali and Algeria in summer. In addition, dust in the Saharan Air Layer is known to interact with the African Easterly Jet and Easterly waves which transport dust across the Atlantic during boreal summer, and it is also acknowledged that the dust itself is likely to play a role in their development and also that of the tropical cyclones which develop from the Easterly waves. Hitherto, few models have attempted to investigate the feedback mechanisms with a fully interactive dust scheme.

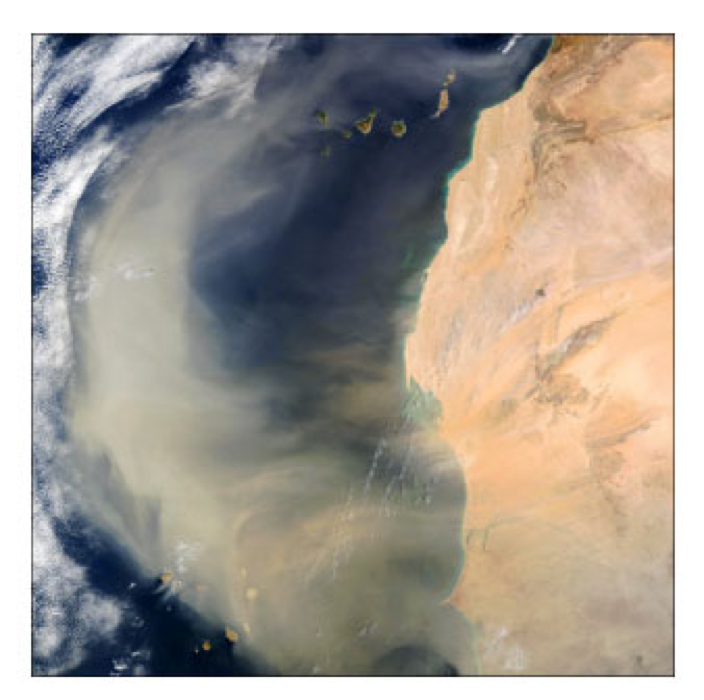

Figure | Satellite image of easterly atmospheric transport of Saharan dust

HiGEM offers a great opportunity to investigate how an embedded mineral dust model behaves in a high-resolution global atmospheric climate model (AGCM), in terms of both the large-scale transport and the smaller-scale features such as dust storms. It has also been possible to investigate the radiative impact of the dust on the model climatology, e.g. temperature, cloud and precipitation, and also on the dust production itself. The method used here was to run a pair of HiGAM experiments forced with AMIP2 sea-surface temperatures for years 1982-2001, one of the pair being advanced in time with the dust radiative forcing included (‘active’ dust), and the other with the dust forcing calculated but excluded from the model advancement (‘passive’ dust). Annual mean dust loadings in the model are ~18% higher in experiments with radiatively active dust than in those with passive dust as can be seen from the figure 1, which shows the 18-year means from the active dust run (top panel), the passive dust run (centre) and the differences (bottom panel). The increase is due mainly to the column warming effect of the dust over the western Sahara during boreal summer, which generates more intense heat lows with stronger winds which lift more dust higher into the atmosphere. This outweighs smaller reductions over Chad and the Sahel, and the Chinese deserts during boreal winter.

The global annual mean radiative forcing (diagnosed from the passive dust experiment) is -1.24 W/m2 at the surface (shown in the top panel of the figure 2), and 0.05 W/m2 at the top of the atmosphere (lower panel of figure 2); however the TOA value varies seasonally from 0.52 W/m2 in March-May to -0.60 W/m2 in September-November, according to the number, size and spatial distribution of the dust particles in the atmosphere.

The model is also capable of generating dust storms on realistic time and space scales such as those arising in the Bodele region of Africa in January-March. The sequence in figure 3 shows the model column dust loadings and 925 mb winds at 12 UT for 1-8 February. The strengthening of North-westerly winds is caused by a weak region of high pressure drifting eastwards across Algeria and Libya. Aerosol optical depths calculated from the model become as high as 4.5 as the dust storm passes, which agrees quite well with available observations.