The hydrological cycle is a fundamental link between components of the Earth system: atmosphere, hydrosphere and biosphere.

Globally it is well understood, is fairly stable globally and annually, but its connections with the other components make it very variable in time and space. This complexity explains the difficulty climate modellers encounter to represent it properly in climate models used for the IPCC assessment reports (Koster et al., 2002). In fact, the hydrological cycle is associated with storm tracks (as storms determine some regional rainfall events), El Nino events (through their global links), NAO phases (linked to regional atmospheric moisture budget). Evaporation and runoff are strongly determined by local land surface-atmosphere interactions (via land cover and orography). Aerosols also can have a large effect by changing radiation, the main driver of the water cycle. Although a change in the hydrological cycle would have little effect on the global ocean circulation, it can still play a role in the overturning circulation, mainly along coastlines if a different quantity of freshwater is discharged into the oceans. These areas of research, also within the HiGEM and UJCC projects, offer a huge opportunity for better understanding the hydrological cycle and its interactions, which could improve its representation, also important for future world water resources management decisions.

Many projects (i.e. under Global Energy and Water Cycle Experiment, GEWEX) have been working on the hydrological cycle in order to continually refine its quantification (Trenberth et al., 2007) and predict changes in the global and regional hydrological processes by developing or analysing global reliable datasets (GPCC, TRMM, GPCP, CRU for precipitation; GSWP2, Fluxnet, GLDAS for land surface fluxes; GRDC for runoff). However, due to computing limitations, the focus of modelling research has been mainly to understand the water cycle on specific aspects or over certain regions only, using high-resolution regional models. Within the UJCC-HiGEM project, the use of supercomputers, such as HPCx, HECToR (UK) and the Earth Simulator (Japan), permits to explore small-scale processes in global AGCM/CGCM as it has never been done before.

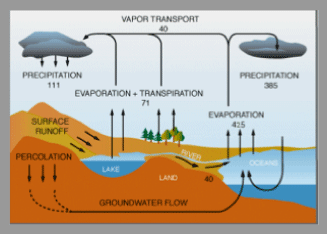

Figure | Schematic illustration of Earth's hydrological cycle

In this study, we aim to use such high-resolution tools to study the following questions:

- What are the controlling processes of the hydrological cycle over land?

- Are global and regional mean precipitation, variability and extreme events affected by resolution?

- What are the impacts on other components of the hydrological cycle over land?

- What is the role of soil moisture within the hydrological cycle?

- Do atmosphere-land surface interactions depend on resolution?

So far, the results show that the global mean hydrological cycle does not improve in high-resolution models due to an overestimation of the radiative forcing, which strongly biases the water cycle at all resolution. This bias is believed to be due to a lack of clouds in the models. Regionally, however, the low horizontal resolution model is incapable of including sufficiently realistic orography, resulting in a spread of precipitation, as shown in the figure below over the European alpine region. It also cannot capture the precipitation extremes, due to poorly resolved convergence and vertical motion. The high-resolution models on the contrary generally tend to represent the spatial distribution of precipitation more accurately, concentrating rainfall near mountain peaks and along coastlines (see figure). The snowmelt timing is also well improved due to the higher elevation of orography. These effects have a positive impact on the representation of river flows around the mountains, whose seasonal cycle is determined by precipitation events in winter and autumn and snowmelt feeding river basins in spring. High-resolution models also simulate less frequent but more intense precipitation events. This intensity/frequency relationship should have a strong impact on the global hydrological cycle if the results were not biased by too much drizzle precipitation and too little dry events, a common issue amongst GCMs. A more in-depth study is needed to understand the impact of this bias on the hydrological cycle.