Extreme weather events, including tropical cyclones, heavy precipitation, drought and heat waves, can lead to huge socio-economic losses.

Hurricane Katrina, for example, led to the loss of over 1800 lives, and over $80 billion of damage. The insurance industry, and risk management in general, is particularly sensitive to weather-related catastrophic events, and the impact of climate variability and climate change on extreme weather events is of great concern to this industry. Catastrophe models are risk assessment tools used to estimate the possible financial loss due to a particular hazard, over a given time period (typically one year), for a particular exposure (e.g. property/business portfolio).

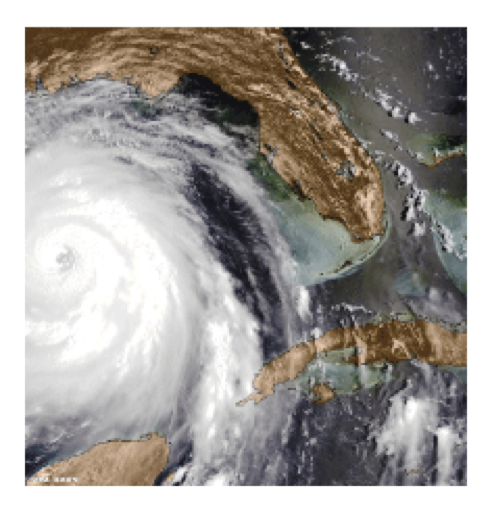

Figure | Satellite image of a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico basin

Catastrophe models provide loss estimates by basically overlaying the properties at risk with the potential natural hazard. The hazard component of a catastrophe model is traditionally a statistical model, relying on historical data to provide probabilistic information about the future likelihood and impact of catastrophic events, including information about phenomena frequency, location, and severity. This stochastic approach assumes that the climate is a stationary system. However, the climate system is non-stationary, displaying variability on multiple scales, which is shown to have an impact of extreme weather activity, such as tropical cyclones. A shift in the state of the climate with anthropogenic climate change would add to the invalidity of this method. The risk management industry is now beginning to see the importance of incorporating dynamical climate modelling results into their weather-related catastrophe models. We are beginning to investigate ways in which extreme event simulations could be used as a basis for the hazard component of a catastrophe model instead of relying on primarily on historical data. Because of the complex nature of the climate system, and the interdependence of difference modes of climate variability, it is important to study small-scale weather events in a global context.

But can global climate models represent extreme events, such as tropical cyclones, and their impacts? The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report states that a resolution of less that 100km is required to begin to simulate tropical cyclones. Using a feature tracking methodology developed at the University of Reading by Kevin Hodges (see Hodges 1994 for further details) we can see that GCMs developed through UJCC are now able to simulate realistic tropical cyclone-like features, a very important achievement in global climate modelling. The tracking methodology is being used to assess aspects of tropical cyclone activity including genesis and lysis regions, track paths, vertical structure, wind structure, and related precipitation. GCM simulated tropical cyclone tracks and structure are in good agreement with observations and reanalysis. However, due to spatial and temporal resolution limitations, the intensity of the storms, important for impact studies, are not well simulated. Identification of the most destructive winds requires capturing, for example, ten-minute sustained winds, on a localized scale of several kilometers.

To gain impact-relevant information, we are working to combine information from high-resolution track simulations with storm ‘footprint’ information from ultra-high resolution (1-5km) tropical cyclone simulation case-studies. Additionally, by simulating a climate with increased carbon dioxide or higher sea surface temperatures, in line with current trends, we can see what may happen, for example to typhoons in the west Pacific, with a changing climate. These simulations will not tell us how many tropical cyclones we will get next year, or where they will strike, but the statistical information will give us an estimation of how tropical cyclone activity, in terms of frequency, severity, and location, is likely to change.

The aim is to introduce this information into catastrophe modelling so that insurance premiums may take into account the impact of climate change and climate variability. Over the next few years, we expect these simulations to improve our and the insurance industry’s understanding of the impact of climate variability and change on extreme weather and importantly the associated uncertainty – essential information for catastrophe models